By Megan Amato

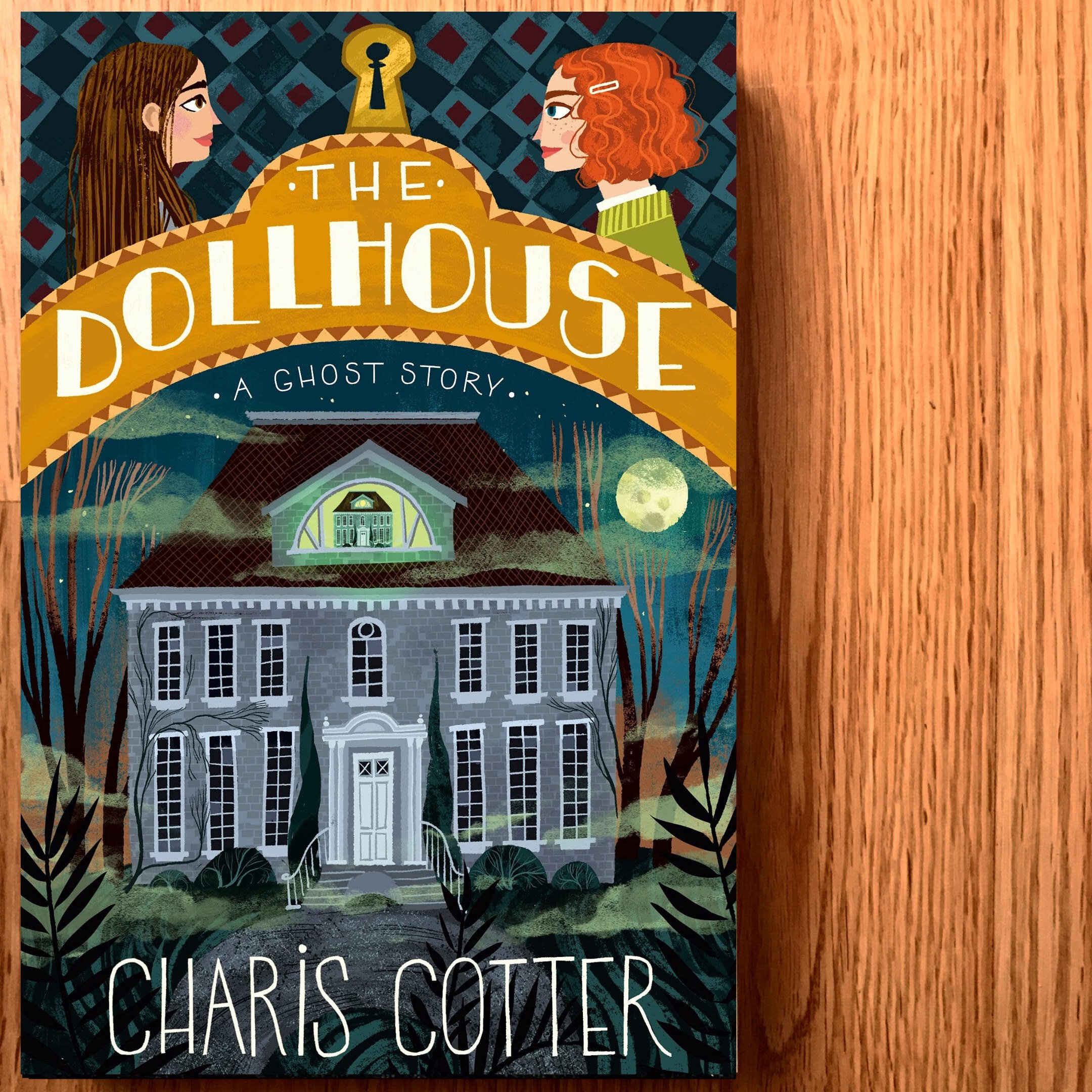

After nearly three decades of declaring my apathy towards horror to anyone who will listen, this past year or so has proved that I just hadn’t explored the genre enough. I should have known better—I tell the same to those who say they hate romance. Gothic horror and ghost stories both delight and spook me, and Canadian author Charis Cotter’s middle-grade novel, The Dollhouse: A Ghost Story, was no exception.

On their way to her mother’s new job, Alice woefully wishes for a more attentive father and imagines the train crashing when it halts abruptly. Sore and a bit dizzy, she meets Mary and her sweet, child-like 16-year-old daughter Lily when they arrive at the house. They explore the home against the cantankerous owner’s wishes and discover a dollhouse in the attic, nearly an exact replica of the house. Soon after, Alice begins to dream of the dollhouse’s creation and a mischievous girl named Fizz and her sweet, child-like older sister Bubble. When a man like her imagined father shows up, real and dream life blur as happenings in the dollhouse appear in her waking world and vice-versa. She demands an answer from smug-faced Fizz, who tells Alice that her train accident was much worse than thought—she died. A distraught Alice denies this, but too many events add up. Was her concussion causing her to hallucinate, or was she the ghost haunting Fizz’s world?

The Dollhouse combines many classic horror tropes—secret rooms, creepy dolls, ghosts that only the protagonist can see, and a plausible explanation mixed with a hint of the unexplainable—and delivers them in a mysterious package that pulls the reader into the story. I loathe when adults critique children’s books with adult book parameters. While the plot progression is a tad predictable, it didn’t detract from my enjoyment of the story, and I think middle-grade readers will enjoy guessing what is going on in that spooky house. I found the development of the story well done, and I think many of the themes (cancelled plans, divorce, lack of control, adults not listening to them) are ones that many young readers can find relatable.

Despite my enjoyment in this story, I did have one major gripe with it: how the developmental disabilities of two of the characters, Lily and Bubble, are written. While I understand that their mirrored traits provided similarities between the protagonist’s real world and her dream/doll world, it came off as a stereotype. Lily’s otherworldly and “off with the fairies” qualities made my hackles rise as it is a common and harmful trope often written into characters with developmental disabilities. However, instead of writing it off for this problematic representation, I think parents should talk to their kids when issues arise in books so children and young adults can think critically about what they are reading.

Despite this glaring issue, I do think that middle-grade readers of ghost stories and fans of Neil Gaiman’s Graveyard Book or Coraline alike will enjoy this spooky tale.

Thank you, Penguin Random House Canada and Tundra Books, for this copy in exchange for an honest review.