By Anusha Runganaikaloo

Content warning: sexism, racism, Islamophobia, child abuse

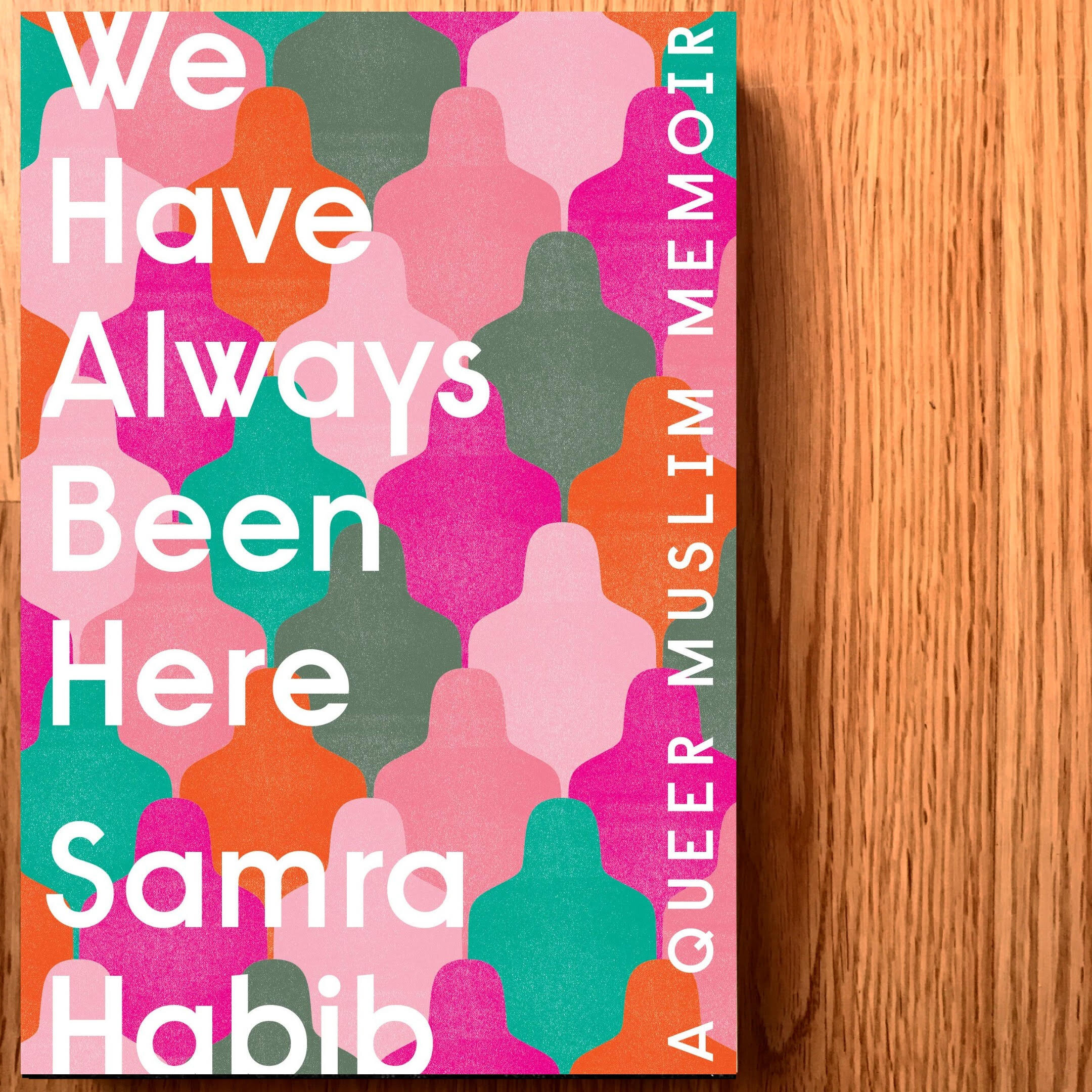

We Have Always Been Here: A Queer Muslim Memoir is the story of Samra Habib, a Toronto-based writer, photographer, and activist. It is a tale of resistance in the face of oppression in one’s homeland, of exile and resilience—but beyond that, it is a one-of-a-kind book that celebrates queer Muslim identities around the world.

The author starts by recounting her childhood in a working-class neighbourhood in Lahore, Pakistan. Nostalgia and trauma are inextricably tangled as, on the one hand, she recalls exuberant family reunions, or mornings spent singing and baking with her mother and sisters in their one-bedroom house while her overbearing father was away at work; and on the other, rampant sexism, femicides, and fearing for her life as an Ahmadiyya Muslim in a country where her community was, and still is, persecuted by the Sunni majority.

At thirteen, the author moves to Canada with her family—and mysteriously, her first cousin Nasir, who is ten years older than she is. Amid a flurry of appointments at the welfare office, struggles and humiliations, encounters with bullies at her new school, intensive ESL classes, and tremendous efforts to adapt to her new environment, she learns that her family has arranged for her to marry Nasir.

The teenage Samra sees her childhood dreams fall apart as her parents and Nasir become more and more controlling, so that she only finds solace in school and books. Ultimately, this is what saves her, as she wins a scholarship to study journalism at Ryerson University. Around that time, we also witness her first act of open self-assertion when she dissolves her marriage to Nasir, challenging her parents’ authority and getting ostracized by her Ahmadiyya community.

From then on, we follow Samra as she searches for herself as a young adult, repeatedly using the dysfunctional coping mechanisms she has grown up with and dealing with incomprehension as a first-generation immigrant.

Slowly, she manages to carve a place for herself as a fashion journalist and dares to come out as queer. However, one thing is sorely missing from her life: spirituality. This realization propels her toward a journey to reconnect with the religion that she distanced herself from so many years ago. It is finally in a queer mosque, a place of acceptance and openness, that she comes full circle and reconciles with who she truly is, a queer Muslim in all her glorious uniqueness.

The strength of this book lies in how it handles complex issues such as family dynamics and religious identity. The author never falls into clichés or extremes. Her parents’ ambiguity and redeeming traits are well portrayed: paradoxically, they are conservative but almost feminist in their fight for their daughters to have the finest education. And, later on, in their own way, they end up accepting Samra for who she is. Furthermore, instead of rejecting Islam, she reclaims her religion and makes it her mission to show the world how queer Muslims are empowered by their faith.

That being said, I could not help but notice a few inconsistencies, such as the author claiming that she was coming out for the first time, or was visiting the USA or Montréal for the first time, when she already had earlier in the story. However, these are minor flaws, and I definitely recommend this edifying read to anyone who wishes to explore the challenges faced by diasporas from a very original standpoint.