By Evan J

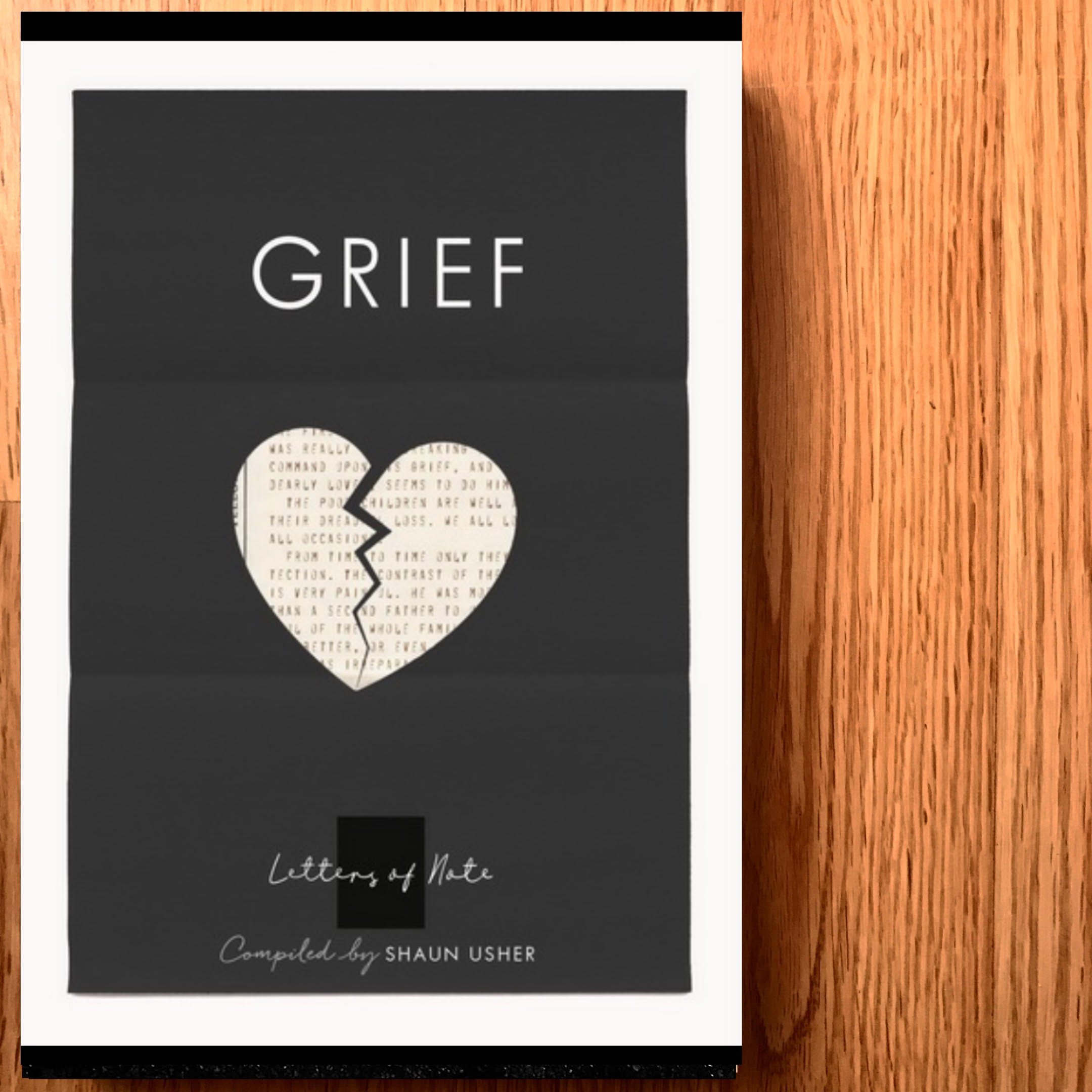

Grief is a collection of letters compiled by Shaun Usher. The book belongs to the Letters of Note series, a collection of small books of collected letters, compiled by Shaun Usher about topics such as war, mothers, cats, and more.

Each letter in Grief was written by a person of historic importance, such as Audre Lorde, Kahlil Gibran, Helen Keller, Virginia Woolf, Albert Einstein, and Abraham Lincoln. The letters are predominantly addressed to a friend or family member of the famous figure, often about the recent loss of a mutual acquaintance. And as expected, the variation of content, of distress, and of tact is remarkable. Many letters speak to spirituality and the brevity of the spirit’s time in the body, such as Benjamin Franklin’s letter “A Man Is Not Completely Born Until He Be Dead.” While other letters, such as the letter written by Eung-Tae Lee—written around 1586 and discovered on her husband’s tomb during an archeological excavation in South Korea in 1998—are burdened by that denial stage of grief, the widow pleading for her husband to visit her in a dream and offer guidance on how to live without him.

So what is this book for?

Grief can cause life to feel like treading water in an ocean. Every second, you’re just trying to stay afloat. And it is the ocean, so it is polluted with scraps of garbage floating by every so often, but there is rarely anything of use, rarely anything to help you stay afloat. Every so often, you pass by a giant ship, something named The Brothers Karamazov, or Hamlet, but the ship is so large, the walls of the hull so tall that, in your tired state, it’d be impossible to climb aboard, so you don’t even try. All you’re really looking for is something small and easy to grasp—a lifebuoy ring, maybe even an inflatable dingy, something you can tip yourself into without a struggle. Something to give you a break from the sharks nipping at your toes. And this book, Grief, that’s what it is: a raft, something to help a grieving person, to help someone treading water. The book is not meant to be a rescue, but it can be a little bit of assistance; a little floatation device helping a person out of the ocean of grief.

So what should you do with this book?

You offer it to someone who has recently experienced a loss. But first, you read the book yourself. You earmark the pages you think that a grieving person might benefit from reading. You annotate the pages with your own comments. You make the book one part historical and one part personal. So that when the book reaches the grieving hands, that person knows that you’re not just handing them a book of letters, you’re offering to hold their hand and read along with them.

Thank you, Penguin Random House Canada, for the complimentary copy in exchange for an honest review.