By Lindsay Hobbs

Content warning: death, illness, hospitalization, racism

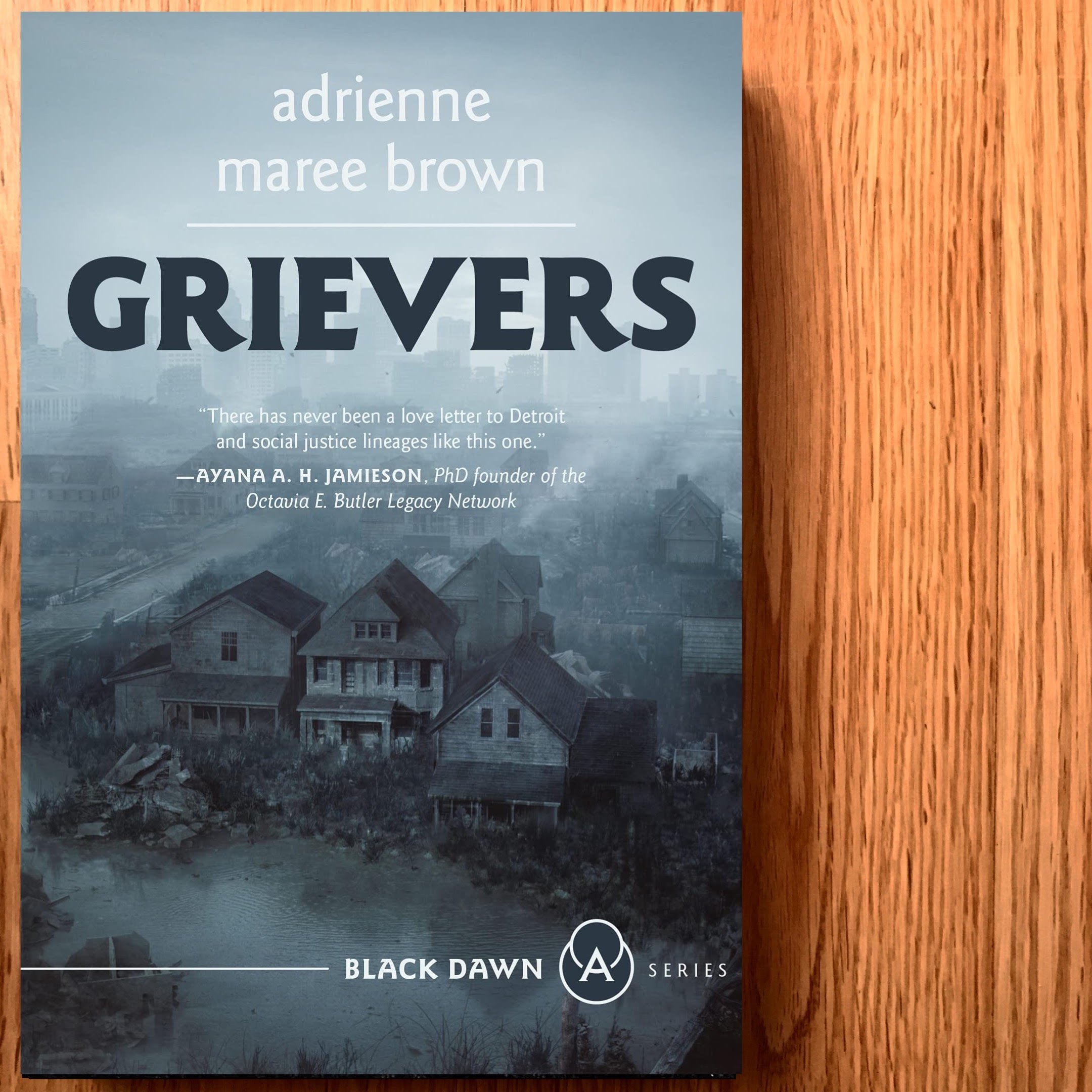

Grievers is a quiet story with deep, unsettling roots. It is at once an astute portrayal of grief and loss, an invitation to engage with ideas of death and renewal, and a love song to the Black communities of Detroit.

When we meet our protagonist Dune, she is struggling to heft her mother’s body, heavy in death, into their backyard. She has built a makeshift pyre and sits vigil over her mother’s cremation. Here begins the story, which then weaves back and forth in time, showing us in lovely and precise language all the details that have led up to this moment and then moving beyond.

Dune’s mother Kama is patient zero of a sickness that will eventually be labelled Syndrome H-8. It hits people out of nowhere, stopping them abruptly in the middle of their lives, rendering them conscious but nonresponsive, with expressions that look like extreme grief on their faces. No one recovers from H-8.

“There was a deeper stillness, a giving up way down in the nervous system. The look on the faces of the sick was usually somewhere between horror and immense longing, the way the word ‘why’ looks when something precious and irreplaceable dies.”

The city grapples with what is happening slowly and clumsily. In a scenario that will feel familiar to us, there are attempts at curfews, masking, social distancing, and enforcement by police. How H-8 is transmitted remains a mystery, and conspiracy theories vie with unsuccessful attempts at research. What is apparent to everyone is that H-8 strikes only Black people.

Dune’s story follows her through the stages of her grief, starting with acute inertia and despair, moving through her efforts to remain connected to her family members via the books and projects they left behind, and finally, on to her growing commitment to document the sick when she finds them in the streets and their abandoned houses. Her own survival is braided into these processes as she learns to follow the rhythms of the seasons, to forage and identify and preserve food, and to move through the empty streets with purpose. These every day and homey aspects of the novel are soothing to read, much as they must have been soothing to Dune to enact.

But as tempting as it is to stay cocooned inside, it is not truly an option. H-8 is steadily ravaging Dune’s city and community. Grief, it seems, is the key to this syndrome. Although there are no explicitly stated resolutions to the questions of what and why, in the novel, it seems clear that H-8 is a sort of manifestation of the injustice, and at times, the sorrow of being a Black American.

“‘Black people. H-8 takes Black people out of ourselves. To…grieve?’

They stood together, quiet, feeling the tender logic in the mystery. Of course Black people were dying of grief.”

Yes, there is a tender logic to this. Anyone who has been paying even the smallest amount of attention to the world can see that. With this novel, author adrienne maree brown, activist and writer-in-residence of the Emergent Strategy Ideation Institute, takes the reader by the shoulders and gently shakes them. The victims of H-8 may not wake up, but we, the readers, still can.

Dune comes from a lineage of women and men in the social justice movement, and it is in this context that we see her home city of Detroit. Understanding the legacies of work that marginalized communities have always done is crucial to reading this story. Fighting oppression and dispossession is work layered with heartbreak, and within Kama, there had always been a necessary core of rage that Dune herself shied away from. Despite being raised in a socially conscious home, she spent a lifetime tucking herself away from her family’s passions. Dune’s grief is now complicated not only by regrets but also by a realization that with her mother gone, so too is a certain tether to life.

Left almost entirely alone in a city that is becoming more and more ghostly, Dune must figure out how to tether herself to life. Her project thus becomes the documentation of the sick and of their pain, and a dogged, steadfast commitment to others that doesn’t waver—even when that commitment means changing soiled adult diapers, cremating family in the backyard, or tucking loved ones who have been taken by H-8 into their beds so they will have some small comfort in their coming deaths. Dune opens herself fully to grief, and her strength grows daily.

Grievers asks hard questions and doesn’t provide any pat answers. It invites us in to this discussion to reflect on how the past informs the present, how trauma can be witnessed and honoured, what can be done to address injustice in the face of such power imbalance, and under what circumstances life can re-emerge and possibly even thrive. It is not an easy read, but it is one that is worth every second.

Thank you to AK Press for the complimentary copy in exchange for an honest review.